Chinese gardens, landscape painting and nature provide new inspiration for our hectic daily lives

2025-09-07

The Chinese “poetical garden”, which binds painting and landscape together, con- tains a “spiritual utopia” that creates new connections between man and nature. These gardens have established free and open spaces in the authoritarian urban society for over three thousand years. In our modern information society, with its rapid circulation of immaterial knowledge, the Chinese garden and natureb can provide room for what the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard calls in-depth reflection. He describes this as follows:

I think what is necessary for thought today requires the exact opposite of the urgency that is imposed upon us; and that is taking your time, letting things take some time, losing time. This is constitutive of all reflection and essential to the activity of thought; it is called “anamnesis.” Time is lost. This activity is indispensable, at least for trying, not to understand, but to retain and bring back what is forgotten in the rush. I think it is very important not to forget.

The particular merit of Chinese gardens, as George Rowley states in Principles of Chinese Painting (1959), is also their assertion that nature can only be un- derstood on its own terms. Retreating to remote areas to escape the turmoil of the world, Chinese poets and painters discovered in nature the spiritual order that they had found lacking in the man-made world and they inspire us to do the same. Their goal is described in the museum in Xiamen as follows: “Only by perceiving and meditating on nature can we human beings communicate with it and achieve harmony between humans and nature to create a better world”. In our times, we can also see that the poetic Chinese garden also contains an ecological message, because it emphasises that respect for nature also includes an obligation to protect it.

Visualisation of these goals can be found in many Chinese gardens

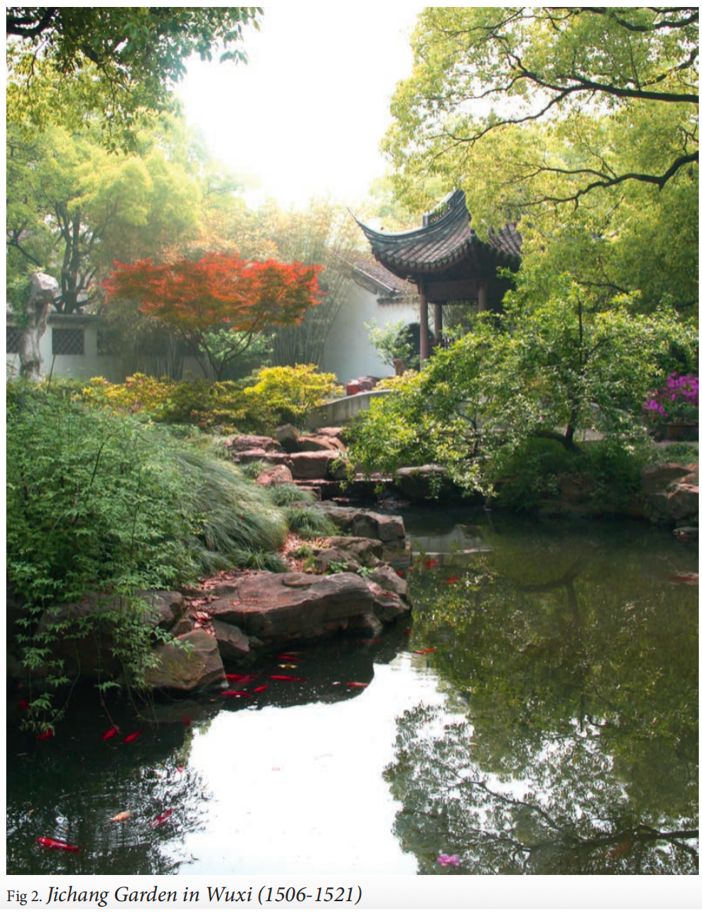

The Yuyuan garden in Shanghai created in 1559 (fig. 1), contains all the elements of a classical Chinese garden: water, architecture, vegetation and rocks, and is characterized by a deep respect for nature. It is, in a way, a microcosm mirroring the macrocosms that inspire us to exist in harmony with nature and the world. The Jichang Garden in Wuxi (1506-1521) (fig. 2) visualises nature in a very poetic, dreamlike way, indirectly inviting us to gain inspiration and broaden our view

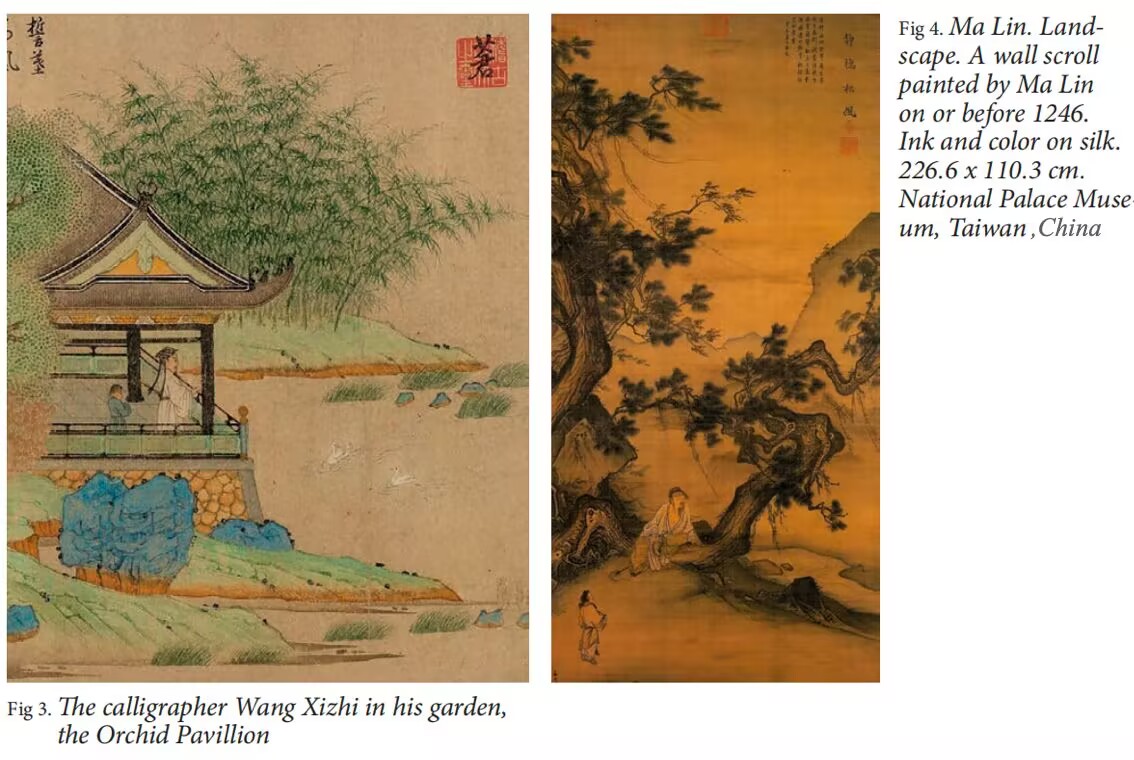

of the world by walking through it. The poet and calligrapher Wang Xizhi (307-365) gathered a group of famous poets in his garden, the Orchid Pavilion (fig. 3) and seated them beside the stream. He floated cups of wine in the current. If the cup stopped alongside one of the poets, he was obliged to drink it and write a poem. In this garden, we encounter the combination of poetry and nature typical of the Chinese garden.

From around 900 AD to the present day, Chinese painters have created visions of landscape depicting the sublimity of creation. Viewers are inspired – in their imaginations – to identify with the figures in the paintings, or to walk on the paths in the landscape depicted (fig. 4). By doing so, they are better able to under- stand its poetic qualities and are thus also encouraged to respect and protect the surrounding nature. One example is a wall scroll painted by Ma Lin on or before 1246 (fig. 4).

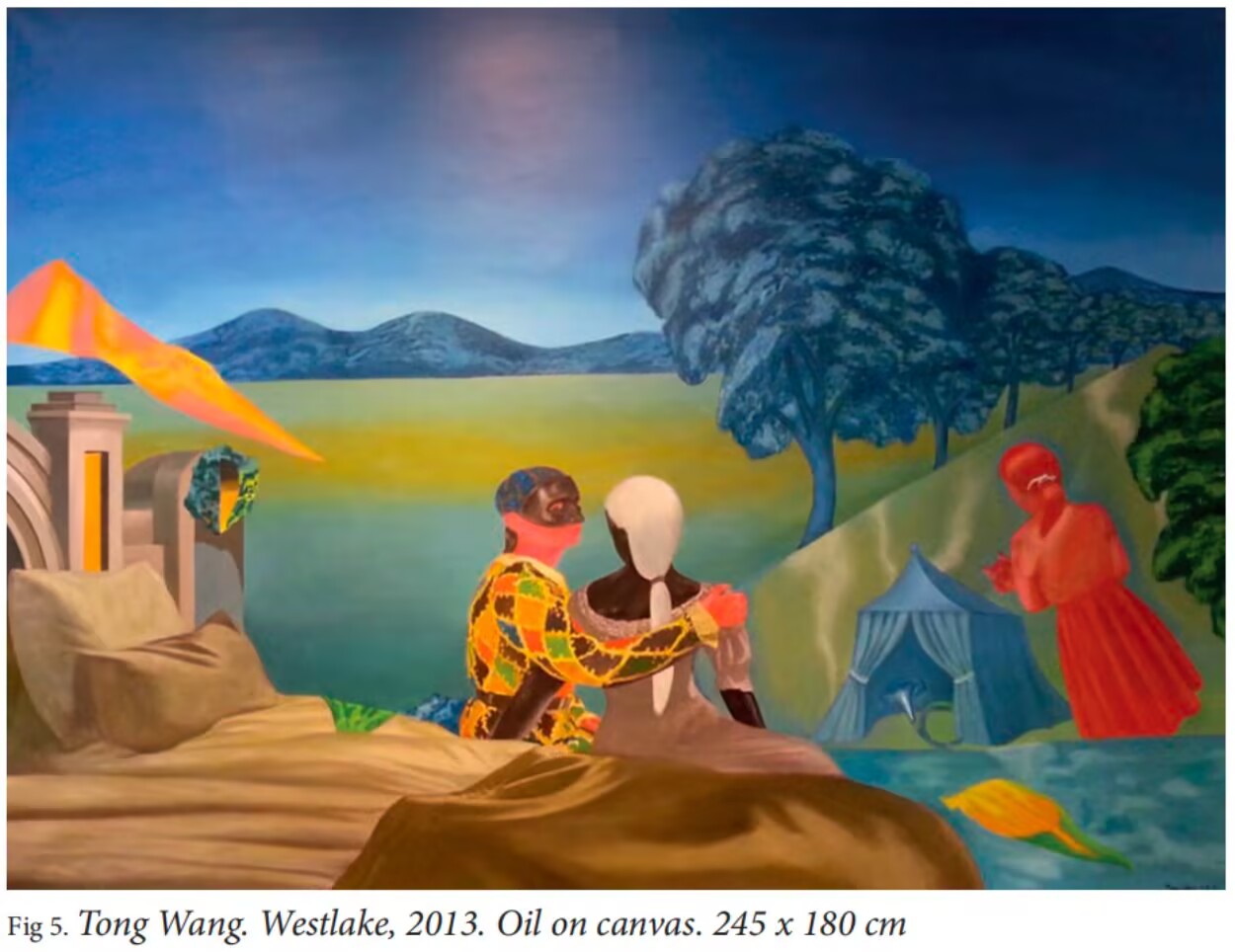

Tong Wang and his wife Lan Lan, who owns the renowned Lan Lan Gallery,

have also generously and cleverly developed and extended the artistic

and cultural connections between China and Denmark. This began in 2000 when the

Art Academy of Inner

Mongolia visited The Royal Academy

of Fine Arts in Copen- hagen. Tong Wang was working

mostly with the Danish and several Chinese Academies until 2003. After 2003,

the CORNER association of Danish artists assumed a prominent place in Tong Wang’s exchange

activities, a collaboration which is ongoing.

On two of the exchange trips

that Tong Wang and Lan Lan generously arranged for a group of artists

from Corner, cultural

workers, and other parts of the Dan- ish arts scene, there was an

opportunity to see the entrancing and monumental landscape that has inspired

Chinese artists for centuries. Foreign

artists are also interpreting this landscape today,

and the artists who participated in the two exchange visits are no exception.

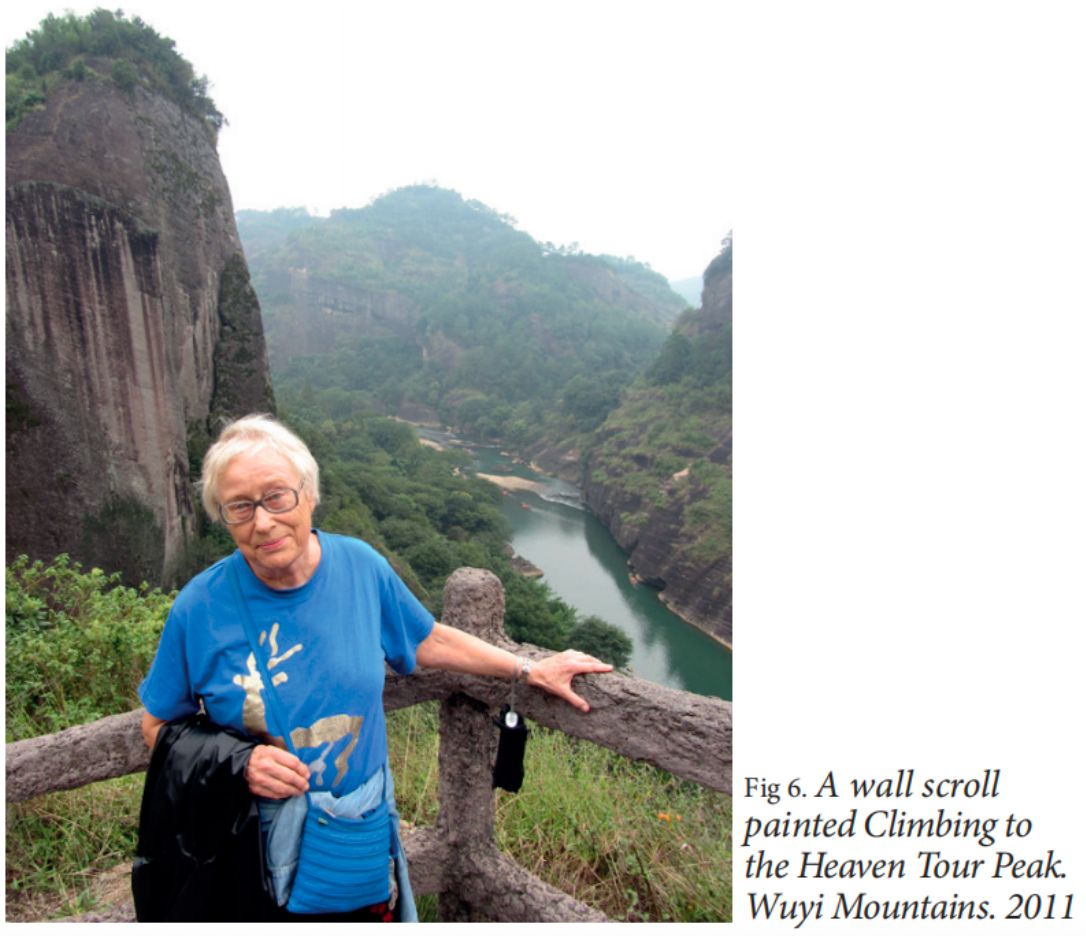

During a journey to South China in October 2011, with exhibitions and lectures in Xiamen, arranged by Tong Wang and Lan Lan, we were provided with the unique opportunity to visit the exquisite Wuyi Mountains. The landscape is impressive, with mountains that have surprising forms and rivers winding their way through the jungle of peaks and rocks. This magnificent landscape is also called a “fairyland on earth”. Neo-Confucianism has been rooted here for 700 years, since the advent of the Chunxi reign in the Song Dynasty. Ancient Chinese literature and art also originated in the Wuyi Mountains. The poet Liu Yong (987–1053), for example, spoke highly of these majestic mountains in his poems. One of the old poems written up there has the following line: “Wuyi Mountains, a place to move you deeply with every breath.” These impressive mountains have inspired artists for over a thousand years. They have painted both the vibrant light and colour and the mist that throws a poetic veil over the monumental peaks. The painter Lars Ravn captures all these features in a photo, which also shows that I have had the pleasure of climbing Heaven Tour Peak (fig. 6).

In November 2014, Tong Wang

arranged a new journey to South China together with Pontus Kjerrman and other

Danish artists. They presented an exhibition with Danish and Swedish artists

in Xiamen. This visit provided fresh opportuni- ties

to study other impressive aspects of the monumental landscapes of South China.

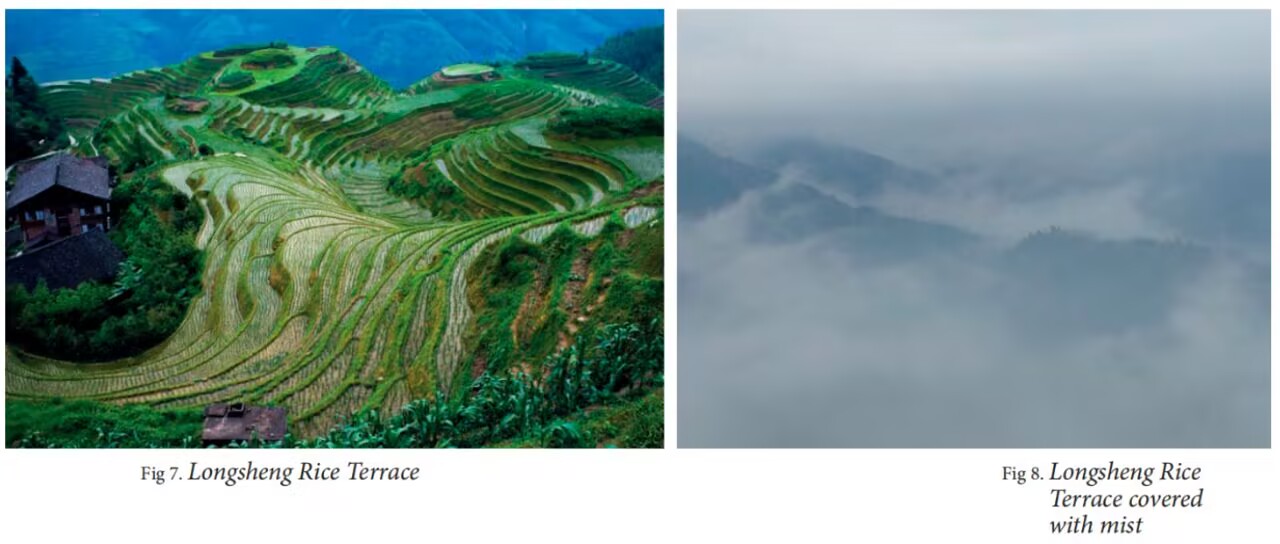

We were particularly fascinated by the unique Longji Rice Terraces (fig. 7), which were mostly

built about 650 years ago. They

were named Longji (Dragon's Backbone) because the terraces

resemble the scales of a dragon,and the ridge of the mountain resembles the backbone of a dragon. But the scen- ery also provides allusions to modern painting, with its labyrinthine patterns of lines. Tine Jacobsen has taken a breathtaking photo of the rice terraces covered by a poetic mist. It almost resembles a Chinese landscape painting (fig. 8).

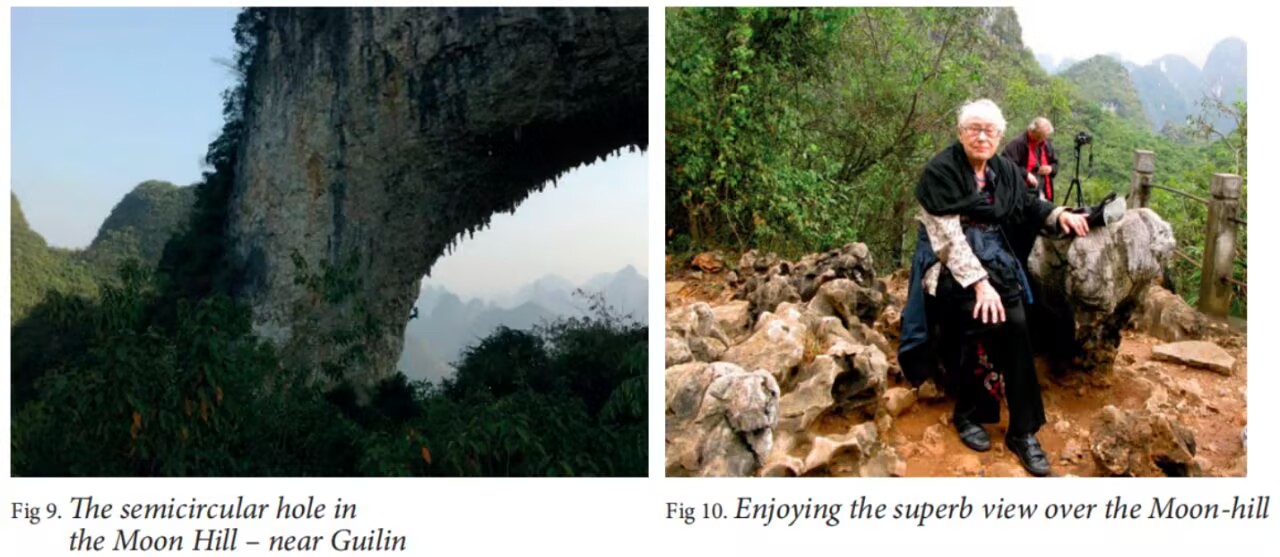

The wonderful journey to the stunning landscapes of South China culminated in a visit to the picturesque city of Guilin. We climbed up nearby Moon Hill, named after the wide semicircular hole running through the hill (fig. 9). I was thrilled to have an opportunity to enjoy the beautiful view of the landscape with the unique Karst peaks partially hidden by mist. (fig. 10).

Working together with Chinese artists and other Chinese personalities in the world of art and culture, experiencing its painting traditions, seeing Chinese gardens and China’s impressive nature, is an enriching experience. It challenges one's own prejudices and encourages a broader outlook. One discovers that Chi- nese culture and art is still characterised by a combination of harmony between the natural world and the human being.

Else Marie Bukdahl