Sensing the Sea - the Exhibition Record

2025-09-06

The exhibition Sensing the Sea was launched in Xiamen, China in the fall of 2024 and aroused great interest. The audience experience became a beautiful humanistic encounter that transcended barriers and distances, and the two curators also learned a lot about how to effectively organize an international art exhibition in China. It was the midsummer of 2024 that a Chinese border officer was examining my US passport. He asked in Chinese where it was issued, and I replied that it's in Denmark. He raised an eyebrow and whispered to his colleagues. My heart beat faster as I awaited the verdict. Meanwhile, my friend and co-curator Tijana Mišković was waiting on the other side of border control, surrounded by a mountain of luggage filled with works for our exhibition. Just when I was fearing the worst - being denied entry, I was finally able to pass through smoothly. This moment marked the beginning of our intense ten-day journey in China, where we will be exhibiting the “Sensing the Sea” at the Nordic Center for Contemporary Art, Xiamen.

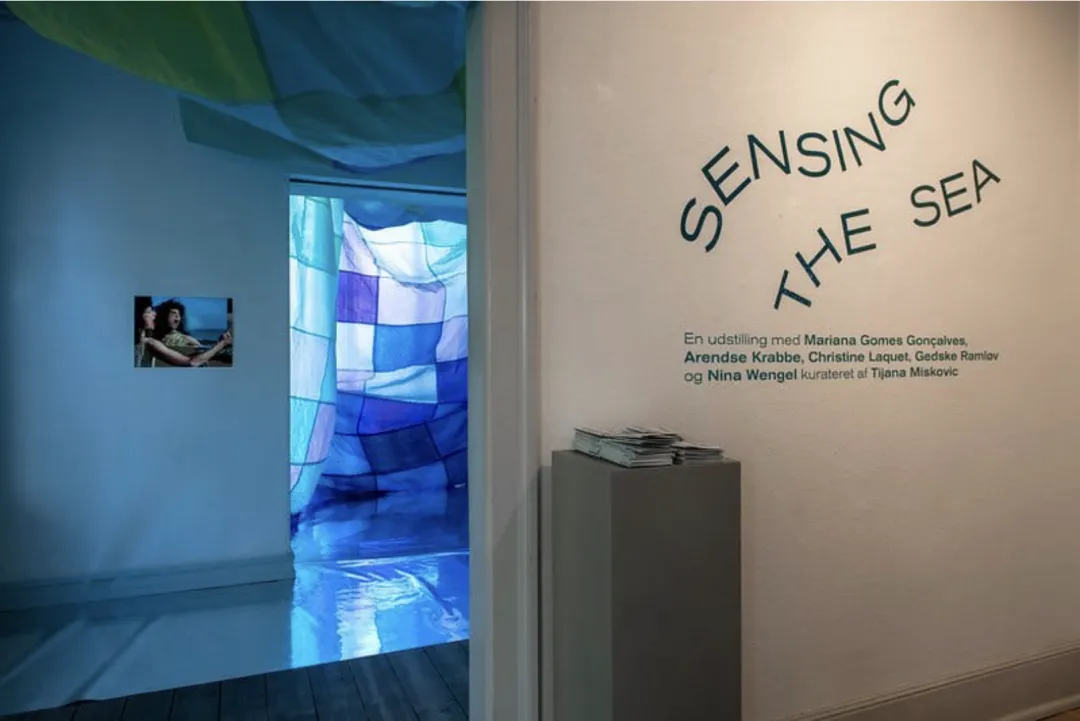

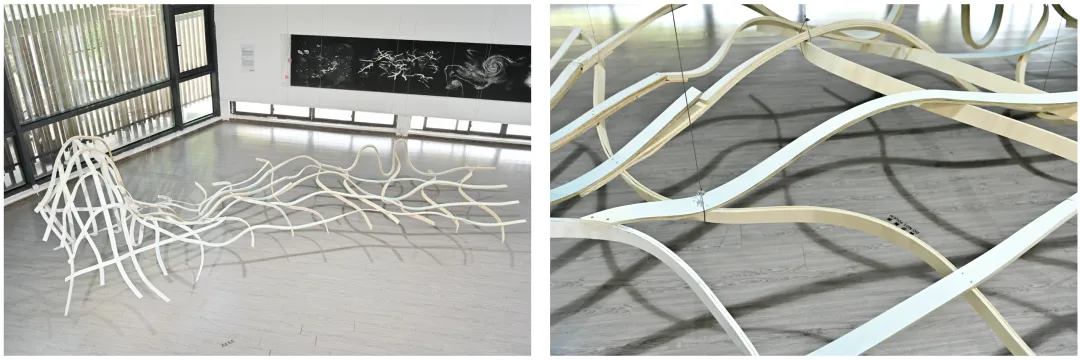

SAK Kunstbygning, Svendborg,Denmark, 2021

SAK Kunstbygning, Svendborg,Denmark, 2021

Sensing the Sea features artworks by Arendse Krabbe (Denmark), Christine Laquet (France), Gedske Ramløv (Denmark), Karen Land Hansen (Denmark), Mariana Gomes Gonçalves (Portugal), Nina Wengel (Denmark), and Rhoda Ting & Mikkel Bojesen (Australia and Denmark).

SAK Kunstbygning, Svendborg,Denmark, 2021

Initially, these artists were brought together for the first time by Tijana in 2021, using the Sea as the curatorial concept and starting point for their common artistic creation, and ended up in an exhibition at the SAK Art Gallery in Svendborg. When I visited this exhibition, I immediately felt that it was very suitable for presentation in the Chinese cultural context.

I proposed the idea of collaboration, and Tijana, who had a long history of curating cross-cultural exhibitions, enthusiastically accepted the invitation. Three years later, namely in 2024, Sensing the Sea was transformed into a new version, based on the imagery and perception of the ocean, building a bridge, in the Chinese southern coastal city of Xiamen, of artistic exchange between Denmark and China.

Thanks to the introduction from my Danish friend, artist Lars Ravn, I was able to connect with the Nordic Contemporary Art Center in Xiamen and its founders and directors Lan Lan and Wang Tong. The art center's strong focus on Scandinavian artists and its frequent programs focusing on the ocean made it an ideal venue for the exhibition. Tijana's long-standing involvement in cross-cultural artistic research, combined with my own background in Chinese studies, laid an important foundation for this project and collaboration.

As curators, we believed that it's crucial for the participating artists to be present during the setting up and opening ceremony, and therefore we strived to secure the necessary funding to cover our own travel expenses and those of the artists.

With supports of the Nordic Centre for Contemporary Art, S.C. Van Fonden, the Royal Danish Embassy in Beijing, the Danish Cultural Agency, the Grosserer L. F. Foghts Foundation, and the Danish National Arts Foundation, we were able to achieve this goal. As a result, six of the eight artists managed to be in Xiamen, and several of them were exhibiting their works in China for the first time.

Meeting with the NAC

One of the most shining moments was translating our curatorial text from English into Chinese. Many expressions in the exhibition and artwork descriptions cannot be directly translated, otherwise the original meaning will be changed. With the assistance of our translator Ruei Li, the translating process added a new layer to the exhibition. Sometimes, the Chinese translation even influenced the original English text, creating an unexpected synergy that helped the exhibition adapt to the Chinese cultural context in a very organic way.

Of course, some linguistic details were inevitably lost during the translating process, which is a common phenomenon between all languages. For example, the pun used by Christine Laquet in her work Don’t you sea changes (2024) cannot be accurately translated into Chinese, so the Chinese title can only be translated as “Have you seen the changes in the sea?(可曾看見海的變化?)”

Another challenge we faced was translating the curatorial copy "invited the audience" into Chinese. The word “embrace” in English can only be translated as “welcome” in Chinese, which is closer to “welcome to the exhibition”. Ultimately, we adjusted our sentence structure to avoid using the word “embrace” altogether. These linguistic negotiations in the translating process not only expanded our understanding of audience's perception but also deepened our understanding of core issues in curatorial practice.

The enthusiasm and thoughtfulness shown by the NAC was also impressive, and all the participating artists felt it deeply. Its team not only provided us with transportation and necessary equipments, but also helped us use online shopping platforms such as Taobao, which were usually difficult for foreigners to operate. In addition, they also carefully provided us with sufficient food and tea supplies during the entire exhibition setting up.

The NAC team also served as a vital local contact for the artists. For example, exhibition coordinator Yatao Zhang helped the artist duo Rhoda Ting and Mikkel Bojesen find a suitable intertidal location for their video work INTERTIDAL SYNTHESIS. The team also facilitated connections for artist Christine Laquet to arrange her residency in Dehua, Fujian, several months prior to the exhibition, where she created a large-scale sculptural installation using Dehua white porcelain.

During our residency, we reflected many times on the extraordinary enthusiasm and commitment we encountered in China. Even within Chinese culture, this level of enthusiasm stands out. We couldn't help but compare this approach to working with Nordic art institutions and discovered a fundamental difference in terms of the concept of efficiency—or at least, in the means by which it was achieved.

In Nordics, art institutions often operates strictly within established plans and structures. This institutionalized approach ensures order and control, but it can also lead to a degree of rigidity. In China, however, working styles are more fluid and intuitive, with many projects often stimulating vibrant vitality and creativity even within limited planning. This adaptability fosters a unique energy that is crucial to the efficient operation of art centers.

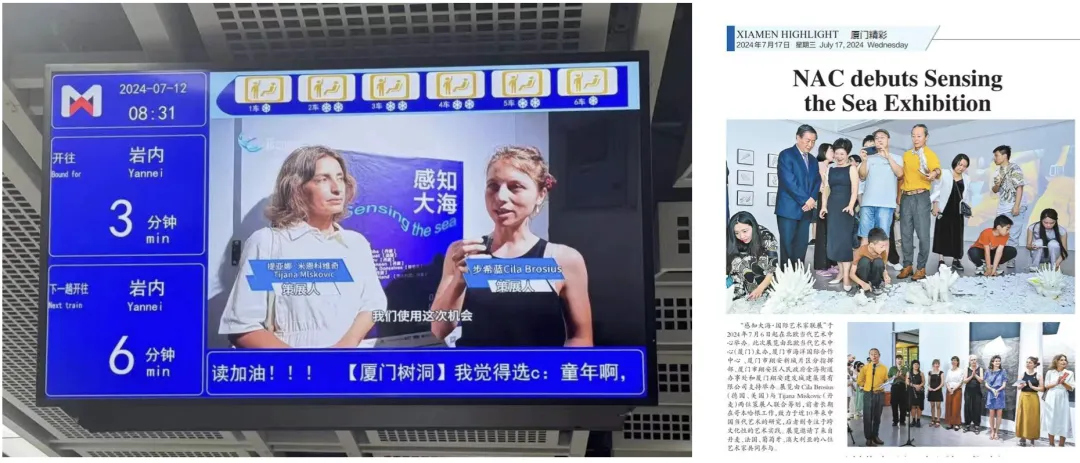

Meeting with the audience

Even long after the exhibition was lauched, the NAC had successfully maintained the exhibition's popularity and continued to expand its influences. Weeks after we returned to Denmark, we continued to receive news about the exhibition, including interviews on local TV, photo and video reports by cultural enthusiasts and influencers, and recommendations on WeChat Moments. We even saw advertisements for the exhibition on the public information screens at Xiamen subway stations.

The audience also showed great enthusiasm for participation. Many of them recorded short videos with voiceover commentary to share their impressions of the exhibition, becoming, to some extent, civilian ambassadors of the exhibition. Even after we returned to Denmark, we continued to receive photos and videos from the audience. This interaction maintained our connection with the audience despite the physical distance.

The promotional measures taken by NAC achieved surprising results. During the exhibition, more than 6,000 people visited, which far exceeded the number of visitors to most Danish art museums during the same period.

We have also witnessed those more private and unique audience experiences. Although they were often being outside the mainstream perspective of exhibition evaluation and communication effectiveness, yet they were often the parts that artists care most about - what they care about was not the amount of exposure, but whether the audience in another culture can truly "see" their artworks.

For example, audience often excitedly exclaimed "ohh Clams!" when they saw Arendse Krabbe and Mariana Gomes Gonçalves's installation Sympathetic Resonance, which is a curtain installation made of clam shells (Chengtzi). They recognized the shells because they were a typical traditional dish in Xiamen, even though the shells used in the work were actually collected in Portugal.

Few days later, we met the sound healer and singer Uanien(元音) and invited her to experience a sound installation made by Arendse Krabbe and Mariana Gomes Gonçalves. This installation, conceptually and technically based on the idea of resonances, seemed to have an immediate effect on Uanien.

She began humming softly on the spot, resonating with the work's frequencies. She stood beside a drum, its surface sprinkled with fine sands that were dancing with the drum's resonance and the sound emanating from the speakers. She placed her hand over her heart, indicating that she was feeling the vibrations of the work physically.

This cultural encounter between a sound installation made by two European artists and a Chinese female singer trained in Eastern sound healing transcended the barriers of language, culture, and ideology. It was an intuitive and beautiful encounter that reaffirmed that even with barriers and distance, people are capable of forming deep connections.

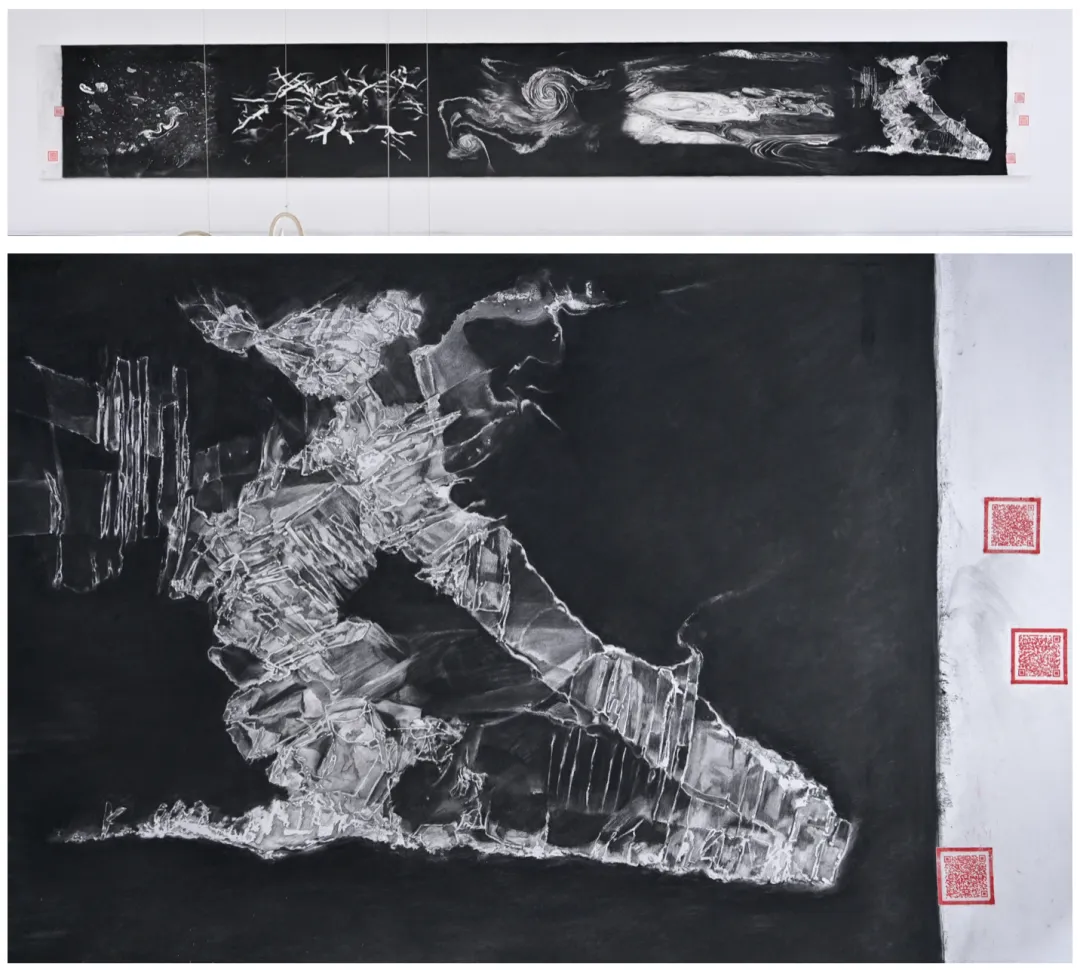

We also noticed how quickly these viewers identified the cultural references to Chinese scrolls in Gedske Ramløv’s paper installation More Black than the Darkness. Her work incorporated references to traditional Chinese ink scroll painting, while presenting challenges of the global ecological crisis from a Western perspective.

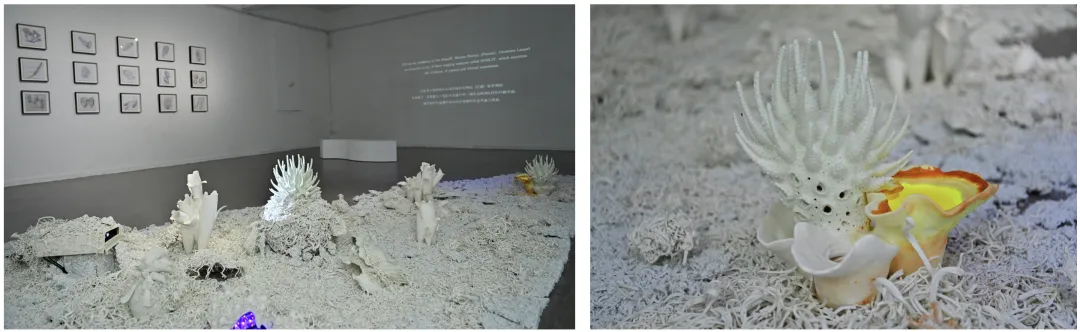

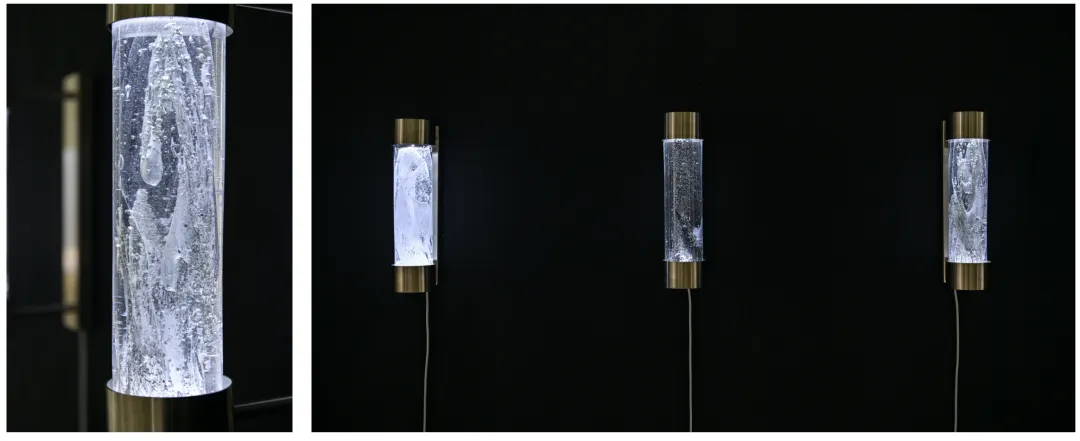

Christine Laquet also referenced elements from the history of Chinese art and crafts. In her sculptural installation Don’t you sea changes?, she used Chinese Dehua white porcelain, aiming to raise discussions about global phenomena such as coral bleaching. Some audiances were surprised to see an european artist working with Dehua white porcelain, and even more surprised that she had known the technique before her arrive in China (Dehua white porcelain is called Blanc de Chine in France). Another surprising thing was that Christine chose scraps from the porcelain factory that were used to be thrown away. This art-making experience helped local audiences realize that local materials they are familiar with have been given some new values and new cultural contexts through the perspective of a foreign artist. We realized that such cultural encounters were helpful developing new understandings and expanding audiences' horizons.

The geometric forms in Nina Wengel's paintings built a bridge between Eastern and Western symbols, which were often closely associated with mainstream religious systems. For Christians, the circle often symbolizes eternity and the infinite nature of God; while in Chinese Buddhism, the circle is associated with the cycle of life and death. Despite different cultural backgrounds, these geometric forms all reflected the universal desires to understand and express the invisible, immaterial and divine existence through visual symbols.

Finally, Karen Land Hansen’s floating sculpture, loosely based on a study of Danish seabed topography, responds to the universal challenge of trying to document the invisible world; while Rhoda Ting and Mikkel Bojesen’s DEEP TIME incorporated sediments dating back over 10,000 years, deeply connecting the audience with geological time long before the emergence of large-scale human civilization, and historical memories that transcended cultural differences.

What We learned

We recognized that being present is crucial not only for facilitating communication and exhibition production, but also for understanding the cultural context, for understanding the importance of an opening ceremony in building professional relationships, and – most importantly – for personally experiencing and documenting audiences’ reactions and reception to these artworks.

We also realized that it was crucial to understand the differences in work processes, norms and standards between Denmark and China. For example, in Nordics, people generally do not use fisheye lens perspectives or over-adjust the saturation of photos in photography; yet in China, such processing is seen as a way to perfect photos. Since we had not explicitly stated in advance that we did not hope to use special effects in the exhibition documentary photos, we had to specifically request that the standard version of the exhibition records be re-photographed. For a Chinese photographer, this might be considered as a dull job, as we explicitly instructed him not to use any special effects and just to make a plain and truthful record.

We also encountered problems with the electronics due to different socket standards and digital connections, the hot weather causing the paint to dry much longer than expected, and many other unexpected situations.

From an European perspective, as Western curators, it can be easy to assume that the only correct way to work is to focus on efficiency. However, when it came to organize the return of the works to Denmark, despite our own professionalism and efficiency, we found that we couldn't do it without the help of the NAC.

Overall, everyone involved in this project was deeply inspired and hoped develop more collaborations between Chinese and European cultural contexts in the future. Therefore, we are also looking forward to returning to China with similar projects in the coming future.

We sincerely thank Lan Lan and Wang Tong, the two founders of the NAC, for their support in making this exhibition possible. We are also deeply grateful to the outstanding NAC team, represented by Zhang Yatao, and for the countless beautiful and warm memories they have brought us.